Our whole world is nothing but a world of grief and misery, and its inhabitants are nothing but grieving and miserable people. The living beings on this earth are all destined for slaughter. The azure heaven and the round earth are no more than a slaughter-yard, a great prison.

↧

Kang You Wei on the world

↧

Edmund Backhouse on religion

Religion is inspired by sentiment, and not by intelligence. It speaks to the senses and thus brings us down to a common level; whereas intelligence engages in disputation and argument.

↧

↧

Oscar Wilde on the Wade-Giles System of Romanization

Chuang Tzu, whose name must be carefully pronounced as it is not written...

↧

Inadvertent Obscenity # 14

Swallow, my sister, O sister swallow,

Swinburne Itylus

Swinburne Itylus

↧

"Five Novels" Ronald Firbank

Ronald Firbank’s novels describe a world which is only adjacent to this one, having many of the features of reality, but a reality which is altogether ‘too much’. In Concerning the Eccentricities of Cardinal Pirelli, there is a class structure, a Cardinal harassed by an overwheening aristocrat, presumptious servants, lavish banquets, and so on. But the overwheening aristocrat has recently had her latest adopted dog baptized in full ceremony in the Basilica, the Cardinal has a crush on an altogether too knowing acolyte, and Madame Poco the wardrobe mistress is a Vatican spy. A world of gossip, barely suppressed scandal, Catholicism of the Scarlet-Whore-of-Babylon variety, and a limpid prose style with roots in the Decadent movement, have ensured for Firbank a place in the pantheon of gay classics. But Firbank is not just a gay writer. He is also one of the great unsung 20th century masters of English prose, a magnificent stylist of the very first rank.

Firbank’s rhetorical devices range between two characteristic gestures: 1) an entirely modern separation of the signifier from its usual signified, opening a new realm of inconsequential beauty, and 2) an extreme use of metonymy, in which smaller and smaller units of language: the oevre, the novel, the chapter, the sentence, the phrase, stand in isolation for something bigger.

He is the master of the double entendre, that most British of rhetorical devices, (but one that needs a French name): In my little garden, I sometimes work a brother. ‘And your Queens, I presume, are Pitchers?

Another device is the use of silences to punctuate an otherwise respectable discourse to bring out the unspeakable:

‘But is he ripe?’ Mrs Thoroughfare wondered.

‘Ripe?’

‘I mean-’

There was a busy silence.

And in the passing silence the treble voice of Tiny was left talking all alone.

‘…frightened me like Father did, when he kissed me in the dark like a lion’: - a remark that was greeted by an explosion of coughs.

The sense of a reality removed from reality is achieved by the use of imaginary titles: the Duquesa DunEden, The Grand Xaymaca; rococo names of people: Mrs Hurstpierpoint, Lady Parvula de Panzoust; and places: Valmouth and Clemenza. Firbank’s characteristic method is to take a name of place: the more euphonious the better, and to transfer it to a person. He is the master of the adjoinage. Consider the made up name ‘Valmouth’, with its associations of the mundane: Falmouth, a small port town in the south of England; and the risqué: Valmont, the villain of Laclos’s Les Liaison Dangereuses, and vermouth, that sin-inducing drink…Saint Euphraxia of Spain, so similar to the real Saint Euphrasia, and yet off by just one letter…

Felix Feneon, the inventor of the three line novel, wrote sentences which were so carefully crafted as to contain within them awhole world, hermetically sealed from anything around it, and containing within itself whole worlds of imaginative possibility. Firbank’s sentences have the same quality. Their matchless rhythms and sounds create marvels of miniature precision. Each one can be lifted from the text and enjoyed in isolation for the jewel-like quality of its images and euphony:

From the Calle de la Passion, beneath the blue-tiled mirador of the garden wall, came the first brooding sound of a seguidilla.

Here and there, an orchard in silhouette, showed all in black blossom against an extravagant sky.

At the season when the oleanders are in their full perfection, their choicest bloom, it was the Pontiff’s innovation to install his American type-writing apparatus in the long Loggie of the Apostolic Palace that had been in disuse since the demise of Innocent XVI.

Likewise, each of the chapters his (very short) novels are marvels of taught construction, in which every element has its crucial role to play. Just as one can enjoy each sentence lifted from its context, so each chapter can be read and enjoyed separately from the whole story.

Firbank has absolutely no political purpose, no wider or deeper meaning. His is a style and a vision entirely preoccupied with artifice and the aural and visual surfaces of language only.

Underlying all the aesthetics is a waspish humour:

The College of Noble Damosels in the Calle Sante Fe was in a whirl. It was ‘Foundation’ day, an event annually celebrated with considerable fanfaronade and social éclat. Founded during the internecine wars of the Middle Age (sic) the College, according to early records, had suffered rapine on the first day of term.

Fraulein Pappenheim was a little woman already drifting towards the sad far shores of forty…

A writer to read with a grin, a chuckle, an occasional eye rolled heavenward at the silliness of it all, and a sustained sense of toe-curling delight at the sheer loveliness of the prose.

↧

↧

A. Symons on the novel

It is by the infinity of its detail that the novel, as Balzac created it, has become the modern epic.

↧

"Against the Day" Thomas Pynchon

There can be little doubt now that Thomas Pynchon is the greatest living American writer –although as Chavenet used to remark, perhaps this is not saying very much, given the lukewarm efforts of his competitors. Pynchon consistently churns out huge monolithic novels bursting with invention of ideas, structure, language and images. Reading a Pynchon novel gives one the feeling that neither writer nor reader is really in control of the material: his novels take on a life of their own through their sheer unwieldiness, their sheer unyieldingness to assimilation, the very magnetism of the parts which make up the whole and which keep the reader gripped even while a sense of that whole slips ever further away. His novels constantly refuse to bow to the literary conventions of pace, structure, characterization, thematic development, cultural reference, propriety and so on: the narrative arc, that bane of American literature originating in the creative writing class, is mercifully alien to Pynchon. Reading him is the closest mental equivalent, I guess, to falling without a parachute or to journeying at great speed without a map or compass, as the reader’s most consistent response is a feeling of slightly hysterical disorientation, best expressed by the modern acronym: WTF!?

The Age of Electrification

Against the Day is a gigantic work, encompassing and describing the fin de siecle in Europe and America: the Age of Electrification. It begins with the Chicago World Fair, one of the earliest uses of urban electrification, and ends with - well, one is not sure exactly what it ends with – but at any rate, it appears to be post WW1. It includes references to major world events that fall between these two markers: the Mexican Revolution, the days of the Wild West, the development of Anarchism and Socialism in the mining industry of Colorado, the development of American Capitalism, the Mayerling incident, the Tunguska event, the Turkish occupation of the Balkans, secret societies and seances in London, the high days of imperialism as the British, Russian and Austrian Empires jostle for control of natural resources, the development of photography, both moving and still, the invention of dynamite and the discovery of relativity. And yet, is it the real world? Chronologies are subtly altered, events are slightly changed, technological developments are brought forward – airships - and exist side by side with entirely imaginary ones – time travel. The world of the novel is a lateral world, set only infinitesimally to the side of the one we think we know.

The plot, such as there is, concerns the doings of the five children of one Webb Travers, a nascent, undeveloped American socialist revolutionary, whose unfulfilled struggle against Them – typical Pynchonian trope there – is carried on in one form or another by his offspring in various parts of the world after he is murdered by two hitmen. Reef, the oldest son and genius with explosives, finds himself in various parts of Europe putting his skills to use blowing tunnels through mountains; Frank stays in the American South West, and finds himself increasingly involved with the Mexican Revolution and various shady business deals; Kit, the youngest son and math genius, finds himself in Yale, then London, then Gottingen, interacting with all the great mathematicians of the day; Lake, the only daughter, shacks up with her father’s killer out of a perverse sense of the perverse.

These characters, and events are linked together in many ways, but chiefly through the device of a dime novel read by one of the characters, The Chums of Chance, the crew of a huge airship on various secret missions through known and imaginary worlds. Our entry into Against the Dayis through this dime novel, a blend of Boy’s Own Magazine, the science fiction of H.G. Wells, Jules Verne, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and the futuristic fantasy art of Albert Robida. It’s the presence of the Chums of Chance that does much to create the kind of steampunk retro feel to the whole book.

This device also brings to the foreground the themes of the book, in that the two realities of the novel: the stories of the Traverse kids, and the story of the Chums of Chance, which one of the Traverse kids is reading, intersect in a number of interesting ways, as characters from the world of the Chums of Chance appear in the world of the Traverse kids (and vice versa), so that one is not actually sure which level of reality is the real one. The characters who intersect with both levels of reality are Merle Rideout, the peripatetic photographer who joins up with the Chums, and then meets Webb Traverse later on in his travels; and Lew Basnight, the private eye from Chicago, who hitches a ride on the airship The Inconvenience, and then is involved with the industrialist Scarsdale Vibe, the man who ordered the murder of Travers pere.

These two worlds, then, are joined hip to hip, one is the shadow of the other, like the bifurcation of image one sees in the crystal known as Iceland spar. Iceland spar recurs throughout the novel, both in the world of the Chums, and the world of the Traverses, and acts as a central symbol for the various sub-themes to do with light (and its absence) which provide the main intellectual backbone of the novel: the intersection of light, time, electricity, waves, advanced mathematics, relativity, particle physics, and a whole host of other nerdish concerns. Double refraction appears again and again as the key element, permitting a view into a Creation set just to the side of this one, so close as to overlap, where the membrane between the worlds, in many places, has become too frail, too permeable for safety…

Pynchon’s main theme in this book, as in all his others, is history. In Gravity’s Rainbow, history becomes a plot in which war is waged by Them against the individual, symbolized by Slothrop’s erections coinciding with the sites of V2 landings. In V, history is a fabric:Perhaps history this century is rippled with gathers in its fabric such that if we are situated at the bottom of the fold, it’s impossible to determine warp, woof, pattern or anything else. By virtue , however, of existing in one gather it is assumed that there are others, compartmented off into sinuous cycles each of which come to assume greater importance than the weave itself and destroy any continuity.Here in Against the Day the metaphor is light and time. If light and space-time are curved, and include a fourth dimension, as all the mathematical sections of the novel posit, then this has interesting ramifications for history. The counterfactual exists alongside the factual, like the shadow of what could-have-been lying against the day of what was, parallel dimensions, occasionally touching each other in monitory pricklings of the invisible. This idea appears in the novelin the presence of the Trespassers - figures who return from the far future to the ‘now’ by means of time travel to warn the characters of what will come to pass; in the presence of déjà vu; in the presence of ‘fictional’ characters living in the ‘real’ world, and vice versa; in the occasional ghostly presence of the airship Inconvenience parked in the sky just beyond the edge of vision; in the slight fudging of the sequence and timing of ‘real’ historical events; in the conspiracy-theory explanations given to historical incidents; the presence of dreams in one world which form real locations in another parallel to it.

Pynchon’s use of history as a theme for his literature largely accounts for the great length and volume of his works, and the way they seem reluctant to ever finish. His novels seem to aspire to the condition of history itself, which has no conclusion, no discernable structure, no single viewpoint. What makes Against The Day different from his previous works is a sense of anger at the way America -and things in general- are going.

Pynchon famously wrote in the blurb to the book before its publication: With a worldwide disaster looming just a few years ahead, it is a time of unrestrained corporate greed, false religiosity, moronic fecklessness, and evil intent in high places. No reference to the present day is intended or should be inferred.

One of the Trespassers says to the Chums of Chance: Your future, [is] a time of worldwide famine, exhausted fuel supplies, terminal poverty – the end of the capitalistic experiment. Once we came to understand the simple thermodynamic truth that the Earth’s resources were limited, in fact, soon to run out, the whole capitalist illusion fell to pieces. Those of us who spoke this truth aloud were denounced as heretics, as enemies of the prevailing economic faith… Pynchon sets most of his novel in an America before Roosevelt’s trust busting activities; and the character of Scarsdale Vibe incorporates characteristics of the great tycoons of the period including J.P. Morgan, and especially the art collector James J. Hill, drawing connections between this earlier lot of scoundrels and the shadowy crooks who run the world today, the Waltons, the Kochs, the Barclays… Pynchon has Vibe articulate the naked truth of rampant capitalism, in quasi Randian viciousness: So of course we use them […] we harness and sodomize them, photograph their degradation, send them up onto the high iron and down into mines and sewers and killing floors, we set them beneath inhuman loads, we harvest from them their muscle and eyesight and health, leaving them in our kindness a few miserable years of broken gleanings. The ‘them’ he is talking about are ordinary people, in other words, you and me.

Pynchon’s anger, however, is not only directed at the capitalists, but at the tenor of life in the USA, both then and now: It was the USA after all, and fear was in the air… the terrible American divide between the hunter and prey…. and at the mind-boggling gullibility which is both a symptom of America’s ills and a cause of it: “You people really just believe everything you’re taught, don’t you?” remarks a British character to one of the Traverse boys. In the final pages of the novel, Webb’s grandson brings home an essay assignment entitled “What it means to be an American”. He writes: It means do what they tell you and take what they give you and don’t go on strike or their soldiers will shoot you down, an assessment that is as much true for the fictional historical America in the novel as it is for the real place now.

One of the points Pynchon seems to making with this novel is the value we assign to various forms of knowledge. One of the most noteworthy and deliberate omissions in a work that appears to include absolutely everything, is the complete absence of literature and philosophy, the humanities, modes of knowledge usually privileged by literary art. In a comprehensive portrait of the fin de siècle/belle epoch, which this appears to be, one would expect mention of the great literature and philosophy of the period, but where is Baudelaire? To be sure, there are echoes of literary tropes - there is a witty passing reference to Oscar Wilde, for example, and some of the Anarchists have a conversation about Bakunin and Kropotkin, but this is little more than simple name dropping, and in a work of this size these are the only two examples that spring to mind. Likewise, the appearance of the ghost of Webb Traverse in a dream to his son does not echo Hamlet so much as reference a vastly older and more universal archetype of revenge, of which Hamlet is only another expression. The characters do not read (except trashy dime novels involving the Chums of Chance), they do not think in terms of the literature and the thought of the past; and more crucially, neither does the narrative voice. The plot - all of Pynchon’s plots- may be seen as a series of interconnected Menippean satires in the style of Swift or Voltaire, but the text would never hint at such a thing itself. Instead, science, especially maths and physics, (in)forms the cultural code underpinning the text. Pynchon seems to be resolutely refusing to acknowledge any literary or philosophical influence by his almost total exclusion of the humanities. At the same time he appears to be attempting to break down the barriers between the humanities and the sciences by his use of a purely scientificcultural code in a work of art, fusing two realms largely considered incompatible or at least disparate. Pynchon’s literary art, paradoxically, creates a space that is almost totally devoid of literature, and in this lies his greatest originality and achievement.

However, this also entails great risks, which I am not entirely sure Pynchon manages to avoid. One of these is the problem of interpretation. As a reader with next to no knowledge (and even less curiosity) about physics, I’m quite sure that whole levels of meaning in the novel remain unavailable to me. For example, the non-linear construction of the plot and the constant switching between different branches of the narrative may have more to do with structures such as the Tessaract or Kepler-Poinsot polyhedrons (isn’t Google a wonderful thing?) than with conventional literary structures. By foregrounding science as a cultural code and eliminating the humanities, Pynchon takes the risk here of placing possible interpretations of his work, its meaning and its relationship to its form beyond the reach of readers without this kind of background knowledge.Sure, one can look things up, but this reduces the ideas in the book to mere information, rather than wisdom. Perhaps that is Pynchon’s point: in the Age of the Algorithm in which we live, when mega-rich Californian nerds can assure a like- minded audience who lap it all up, with all the seriousness and sincerity of a religious cult, that their little gadgets and toys for grownups are life altering and world changing, while the great bulk of the human population of the planet can still not count on constant access to reliably clean drinking water and live in conditions which are still medieval, our wisdom has not kept pace with our scientific abilities and the uses to which we put those abilities. As a species we have never had so much access to information, but we have also never been stupider.

The second and related risk is the notion of seriousness. Western literature largely signals its seriousness by including a cultural code derived from the humanities. A novel of ideas, for example, includes ideas which are largely determined by art and philosophy: ethics, problems of identity, personal, political, social, relationships, history and the individual, our experience of death and God, the problems of consciousness and so on. With an almost total absence of such a code, how does a novel signal its seriousness? Without this seriousness, a novel risks becoming merely a divertissement, a jeu d’esprit. But, can a book that comes in at over 1000 pages and takes at least a month to read really be called a diversion? The great weight and length of the work signal another kind of seriousness, one that asks us to appreciate the abstract beauty of theorems and algorithms and to read history in their light. This is ultimately a work of literature that seeks to liberate us from literature, that has the aim of trying to free us from the thinking of the past and to see that past set against the day of our own time.

In one of the most stunning images of the novel, two of the Chums of Chance get into a time machine and travel into a future far beyond theirs and ours. This is what they see:

Undoubted human identities, masses of souls, mounted, pillioned, on foot, ranging along together by the millions over the landscape accompanied by a comparably unmeasurable herd of horses……thus galloping in unceasing flow ever ahead, denied any further control over their fate, the disconsolate company were borne terribly over the edge of the visible world…

↧

Correspondence # 12

There is a goal, but no way. What we call the way is hesitation.

Kafka

The Way moves on by contra-motion.

Dao Der Jing 40.1

Kafka

The Way moves on by contra-motion.

Dao Der Jing 40.1

↧

Fragment 199

In The Lover’s Discourse Barthes writes about irrational behavior, especially that prompted by love. For Barthes, irrationality stems from the image and the uncontrollable force of language produced by the image- this is the lover’s discourse. Under the signifier D for demons:

In The Lover’s Discourse Barthes writes about irrational behavior, especially that prompted by love. For Barthes, irrationality stems from the image and the uncontrollable force of language produced by the image- this is the lover’s discourse. Under the signifier D for demons:A specific force impels my language toward the harm I may do to myself: the motor system of discourse is the wheel out of gear: language snowballs, without any tactical thought of reality. I seek to harm myself, I expel myself from my paradise, busily provoking within myself the images (of jealousy, abandonment, humiliation) which can injure me; and I keep the wound open, I feed it with other images, until another wound appears and produces a diversion.

For Dostoevsky, irrationality was always self-harming, but only if self- harm is considered from the point of view of rationalism itself, from the dictum of never knowingly acting against your best self interest. And for Dostoevsky, too, this irrationalism erupts as an uncontrollable impulse towards language. Raskolnikov, in the Crystal Palace, blurts out his murder, but his interlocutor doesn’t believe him mainly on the grounds that if he was the murderer, he wouldn’t confess so brazenly to it. Think of all those characters who blurt out the wrong thing at the wrong moment, impelled by the language instinct to lacerate themselves, to make the situation worse, to assert their right to a capricious rejection of Paradise, the caprice of language itself. And think of all the demons in Brothers Karamazov, how Liza blurts out her love for Alyosha, and then prompted by her little demon, says that to be despised is good, expelling herself from her paradise.

Suddenly there are demons everywhere… BK 11.3

↧

↧

William Burroughs on the immortality of the writer

The immortality of the writer is to be taken seriously. Whenever anyone reads his words, the writer is there. He lives in his readers.

↧

"A Lover's Discourse" Roland Barthes

Love has been written and sung about since our species first learned to produce language, and its effects on the emotions, the heart, the personality and the body have been studied, recorded, analysed and celebrated from the dawn of history. What interests Barthes more than these however, is the effect of love on the mind, on the intellect, specifically that part of the mind which produces language. For Barthes, love exists as an outpouring of language: “I’m so in love!” “I love you so much!”, “I love him”, “I love her” etc. Love exists, then, in its most developed form, as an ejaculation, as discourse produced by the lover, whether mental or uttered. What Barthes does is to focus on this discourse, but in such a way as to enact it rather than to analyse it.

Language is either transactional – we use it to do things - or descriptive – we use it to describe things. Either way, it is locked into one or other of these two modes. The challenge for Barthes was to liberate language from either of these two ways of being and to give language a third possibility, that of the truly declarative and expressive; a mode in which language expresses meaning not by referring to things, but by virtue of its own structure. In simple structuralist terms, ‘cat’ means cat not because of any inherent relationship between word and object, but because ‘cat’ is not ‘bat’ nor ‘car’ nor ‘cut’, and because we have agreed amongst ourselves that this pattern of sounds, this structure and no other, shall stand for this and not for something else.

In two works from 1977, Barthes attempted to apply his ideas about language to two of the most traditionally conventionalised genres: the autobiography, and the love story. In both these works he reached for a method that would empty language of its content and bring to prominence its form, its structures; to find a mode uninflected by referentiality or utility: a writing degree zero, in which writing is not about something other than itself.

A Lover’s Discourseattempts to create a discourse about love which does not merely describe love or refer to it or analyse, novelise it, but to simulate it, to dramatise it, to recreate it. As Barthes puts it: the description of the lover’s discourse has been replaced by its simulation, and to that discourse has been restored its fundamental person, the I, in order to stage an utterance, not an analysis. This is not an analysis of love, but a staged utterance. We are to read it as the unmediated thoughts – discourse – of the lover himself.

In attempting to liberate language from its two constraining modes, Barthes has created a highly original structure. Taking as its model the dictionary – another work in which language is not about anything other than itself – the book consists of 80 fragments, each consisting of four elements or layers.

The first layer is what Barthes calls the figure, a gesture, to which all the other elements in the fragment point: No Answer. The second layer is a headword: mutisme/silence,and it is under these headwords that the fragments are arranged alphabetically. The third layer is a sentence which defines the headword and the figure: the amorous subject suffers anxiety because the loved object replies scantily or not at all to his language (discourse or letters). The fourth layer then gives a series of numbered aphorisms in the style of Nietzsche, which in different ways comment on, develop, contradict or exemplify the figure. There is thus a movement within each entry of all the major elements of language: from the phrase and the word, through to the sentence and the aphorism, and ultimately to the text itself.

By organizing the entries in alphabetical order, Barthes avoids the pitfall of editorializing – the arrangement of fragments into some order determined by something outside language, something resembling a narrative arc or personal experience, or more artistic considerations such as pitch or pace. At the same time he also avoids an extra-linguistic ordering according to coincidence or chronology. The alphabet is an ordering system that belongs to language itself. An alphabetical ordering, therefore, maintains the formal purity of the language.

Because language in its purist essence is a structure that only has meaning by reference to itself, each entry includes references to other stretches of language on love, to conversations with friends and lovers, to the great works of European literature on love: The Sorrows of Young Werther, the Symposium, Stendahl’s De l’Amour, Freud, Lacan, Proust and so on. The use Barthes makes of these quotations and the way he illuminates them are one of the highlights of the work. (The only weakness, if we may permit ourselves to be critical of a work so full of wisdom and beauty, is the complete absence of any reference to Shakespeare, surely the wisest and most comprehensive teacher of love in European literature.)

Everywhere, Barthes focuses on the relationship between love and language, the discourse of love. Some examples. Here he is on I-love-you:

I-love-you is without nuance. It suppresses explanations, adjustments, degrees, scruples. In a way – exorbitant paradox of language – to say I-love-you is to proceed as if there were no theatre of speech, and this word is always true, has no other referent than its utterance: it is a performative.

On the scene, or lovers’ quarrel:

It is characteristic of the individual remarks in a scene to have no demonstrative, persuasive end, but only an origin and this origin is never anything but immediate: in the scene I cling to what has just been said.

Or on the way we cover the loved being in language in trying to pinpoint exactly what it is we love about that person:

Industrious, indefatigable, the language machine humming inside me – for it runs nicely- fabricates its chain of adjectives. I cover the other with adjectives, I string out his qualities, his qualitas.

Or the meaning of the lovers tautology: “You are adorable because you are adorable, I love you because I love you.”:

Is not tautology that preposterous state in which are to be found, all values being confounded, the glorious end of the logical operation, the obscenity of stupidity, and the explosion of the Nietzschean yes?

In passing, Barthes occasionally drops these shattering epigrams, as if they have no meaning, no significance, no importance:

Orgasm is not spoken, but it speaks, and it says I-love-you.

Cannot friendship be defined as a space with total sonority?

The third person pronoun is a wicked pronoun: it is the pronoun of the non-person, it absents, it annuls.

Since man has existed he has not stopped talking.

Now, in case this sounds like the laying of the dead hand of structuralism on the living pulse of a poetic emotion; if it sounds dry and intellectual, let me assure you that it is anything but. The book is beautiful, playful, full of arresting insights, new ideas, lyrical and tender, witty, sympathetic, moving, sensual, joyous. In short, it is everything you would expect a book about love to be. And if one reads it when one is in love, truthful and accurate to a powerful degree.

The word is not the thing, but a flash in whose light we perceive the thing.

Diderot

↧

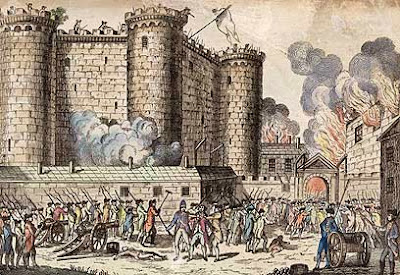

Louis Suleau on the French Revolution

What's the use of your Revolution if it breeds long faces? What's the use of a revolution run by miserable little men in miserable little rooms?

↧

Fragment 3010

He seemed to me then the very archetype of a romantic. His appearance, his blazing, indeed fanatical artistic zeal, his intensity, his grotesque humour all struck me as the incarnation of one of ETA Hoffmann's fantasy figures. His incomparably passionate concentration while rehearsing and conducting, forever reminding me of his fantastical forerunner, Kreisler, made such an impression that I wholly forgot that he made room in his life for other activities and that his name had first struck me as a composer....

Bruno Walter on Mahler...

Bruno Walter on Mahler...

Kapelmeister Kreisler

Drawing by Hoffman

Gustav Mahler

Silhouette by Otto Bohler

↧

↧

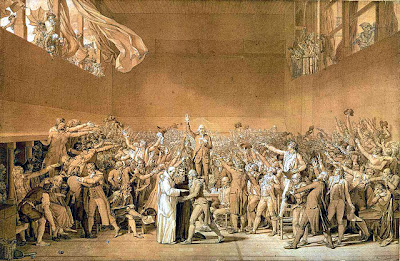

'The French Revolution: A History' Thomas Carlyle

In the opening chapter of his ground-defining book The Symbolist Movement in Literature, the Edwardian critic and poet Arthur Symonds quotes this dictum from Carlyle’s history of the French Revolution: It is in and through Symbols that man, consciously or unconsciously, lives, works and has his being. First published in 1837 – only 40 years after the events it depicts- and around the same time that Ranke and Comte were trying to establish history as a more scientific discipline, with an underlying theory and a rigorous methodology, Carlyle’s History occupies an ambiguous position in historiography today.

On the one hand, Carlyle’s work is still cited as a source in the most up-to-date studies of the Revolution. It’s a must-go-to text for students of the period. On the other, there are those who argue that Carlyle’s methods and project are not empirical enough; that his high-flown, epic, symbolic style undermines any scientific contribution the work might make for an objective understanding of the Revolution. Modern academic historians have done much to lay open the economic causes of the Revolution, studying tax returns and harvest yields etc, while Marxists have given us a framework for understanding the underlying political and structural causes. Against this kind of academic, objective approach, Carlyle’s work reads more naively, more like a novel, or an epic of Revolution, and less like a serious scientific study.

But to hold this view is to miss the point Carlyle is trying to make about history, and to be blind to the very sophisticated awareness the work displays of the difficulties inherent in doing history. And not to read Carlyle is to miss out on the pleasure of encountering one of the greatest works in English of the 19th century.

The French Revolution may be regarded as a prototype of Symbolist literature, a non-fictional Symbolist work avant la lettre. This Symbolism is present in the work in at least two ways: in the theory of history that underpins the text, and in the text itself, the historiography.

1. A symbolic theory of history

Men do what they were wont to do, and have immense irresolution and inertia; they obey him who has the symbols that claim obedience.

As Symonds noted, Carlyle sees man’s propensity to create and interpret symbols and signs as the defining essence of man and fact of history: Man, by nature of him, is definable as ‘an incarnated word’, or in other words, man is a symbol-making creature. His allegiance to or rejection of symbols is held by Carlyle to be a chief driving force of history because it’s man’s adherence to or rejection of symbols that provides the strongest and highest motivation for his actions: Of man's whole terrestrial possessions and attainments, unspeakably the noblest are his Symbols, divine or divine-seeming, under which he marches and fights, with victorious assurance, in this real life-battle: what we can call his Realised Ideals. Carlyle sees history as the operation of various forces, not economic or political as modern academic historians do, but symbolic forces. This is how, for example, Carlyle explains the astonishing victories of the French Revolutionary army against much stronger, much better supplied and organized forces of the Coalition; that the French were fighting for a symbol, for their Revolution, and that it was the motivating power of this symbol, greater than the motivating power of the enemy’s symbols – Monarchy, Order, Conservatism- which led them to victory.

Carlyle describes the whole movement of the Revolution, from the early revolt against feudalism in the late 1780s to its capture by the reactionary and largely bourgeois Directory in 1795, in terms of a gradual movement between various symbols, a movement away from the symbols of Aristocracy of Feudal Parchment to an Aristocracy of the Moneybag. He comments: Fleur de lys had become an insupportably bad marching banner, and needed to be torn and trampled, but Moneybag of Mammon (for that, in these times, is what the respectable Republic for the Middle Classes will signify) is a still worse, while it lasts, and he calls this last symbol: the worst and basest of all banners, and symbols of dominion among men.

At the same time Carlyle is aware of the internal growth and decay of symbols, both as entities in themselves, and of the waxing and waning power of symbols to motivate men and hold society together. Of the former he writes: The Truth that was yesterday a restless problem, has today grown a Belief burning to be uttered; on the morrow contradiction has exasperated it into mad Fanaticism, obstruction has dulled it into sick Inertness; it is sinking towards Silence, of satisfaction or of resignation, marking stages in a symbol’s evolution from an intellectual problem – a truth-, to a belief, to a fanaticism, to an inertness, to a silence. Of the latter he writes how symbols can be exhausted, becoming in effect empty lies or shams, which need to be overthrown. Indeed, he sees this overthrowing of empty symbols and the creation of new ones as another motivating factor in history generally, and in the French Revolution in particular, contrasting the lies of religion under the Old Regime, for example, with the reality of hunger:Behold, ye appear to us to be altogether a Lie. Yet our Life is not a Lie, yet our Hunger and Misery is not a Lie! Symbols can also be emptied of their mysterious content and power to become mere ‘Formulas’, by which Carlyle means abstract ideas such as Constitution, Justice and so on. Carlyle sees history as the interaction between these formulas and reality: What strength, were it only of inertia, there is in established Formulas, what weakness in nascent Realities. In the text, Robespierre is the representative of such formulas, while Danton is the embodiment of reality: with what terror of feminine hatred the poor seagreen Formula looked at the monstrous colossal Reality, and grew greener to behold him. Symbols for Carlyle, then, can also operate in the realm of history as shams, lies, formulas.

Carlyle’s view of the importance of symbols in the processes of history is a corollary of his wider theory of history. Carlyle sees the universe as a chthonic ocean of forces, innumerable and ineluctable, internal and external.Our whole Universe is but an infinite Complex of Forces; thousandfold, from Gravitation up to Thought and Will. Every event in history is the result of an action, and an action is the product and expression of exerted Force. Similarly, each person is a nexus of such forces, so that when men come together to make history, as they did in the Constituent Assembly and the National Convention, the number of forces and the interactions between these forces become necessarily so complex that no objective science can hope to fathom them:

Every reunion of men, is it not, as we often say, a reunion of incalculable Influences; every unit of it a microcosm of Influences, of which how shall Science calculate or Prophesy! Science, which cannot, with all its calculuses, differential, integral and of variations, calculate the Problem of the Three gravitating Bodies, ought to hold her peace here, and say only: In this National Convention there are Seven Hundred and Forty Nine very singular Bodies, that gravitate and do much else, who probably in an amazing manner will work the appointment of Heaven.

For Carlyle, the enormous complexities of history are not something which a scientific, empirical method alone can deal with; they require, in addition, comprehension by a symbolic, historical imagination.

Space precludes us here from entering into a fuller discussion of the interaction between Carlyle’s view of history and his historical methods with those trends that were developing concurrently in Germany under von Ranke. We can say, however, that Carlyle, a student of German culture, was aware of them, and that his symbolic view of history, when contrasted with von Ranke’s more empirical view, is not so naïve as it sounds. Carlyle’s work, like von Ranke’s, was grounded in close readings of contemporary documents, including letters, diaries, contemporary newspaper articles, memoires – including those of Goethe’s, whom he quotes at length- , as well as trial transcripts, minutes of the proceedings of the Jacobin Club and the other various assemblies that met during the course of the Revolution.

Having looked at Carlyle’s symbolic theory of history, we turn now to symbolism in the text itself.

2. Symbolic historiography

Man is a born idol worshipper, sight worshipper.

In his text Carlyle uses various key words to stand for a particular nexus of historical forces. Von Ranke warned against this because he thought that the use of such key terms –leading ideas - circumscribed the historical reality behind them; he believed that the complexities of an historical event cannot be characterized by the recurring use of only one term or idea. But Carlyle, by giving these words capital letters, in effect turns them into symbols, naming them, and thereby allowing the reader, a symbol loving creature, to see them. It is thus, however, that History and indeed all human Speech and Reason does yet, what Father Adam began life by doing: strive to name the Things it sees of Nature’s producing – often helplessly enough.

For example, the origin of the Revolution he sees as arising from the interaction of the two forces which he names ‘Prurience’, and ‘Effervescence’. The pre-Revolutionary scene was ripe with ‘Prurience’ – a word that in the 1830s meant a mental itching or craving, as well as propensity towards lewdness. He traces how this manifested itself both in the corrosive ideas of the Philosophes and Enlightenment thought; in the increased focus on pleasure in the life of the court, which created an unbridgeable gulf between rulers and ruled as well as putting an unsustainable strain on the nation’s finances; and in the scandal sheets and erotica which circulated freely in Paris in the late 18th century, engravings featuring the Queen in lesbian orgies and so on. Acting as spark to this gunpowder is ‘Effervescence’, which he describes as the propensity in the Gallic character for the sudden eruption, for the passionate gesture, for noise and fuliginous fury. Carlyle ascribes the various revolts that happened throughout France in the terms of ‘Effervescence’, noting, in his account of the sugar riots in Paris in the summer of 1792, for example, how the secret courses of civic business and existence effervesce and effloresce, in this manner, as a concrete Phenomenon to the eye. In the text, ‘Prurience’ and ‘Effervescence’ become symbols of two forces whose interaction was the cause and spark of the Revolution.

Symbolism in the discourse also appears in a number a recurring devices, such as the extended and repeated similes or metaphors Carlyle employs for the Revolution itself: a sand palace disappearing into a whirlwind, a fireship sinking with all hands. Another device is the repeated epithet, which accompanies the names of the key figures of the Revolution -like Homer’s heroes - to remind the reader who they are: Robespierre is always seagreen, Huguenin ever has the tocsin in his heart, Maillard is always the famed leader of the Menads…

Carlyle knows that the reader is a person in history just as much under the influence of symbols as the personages in his history of the Revolution are. Man, with his singular imaginative faculties, can do little or nothing without signs, which is one of the reasons why he employs a symbolic, epic, novelistic mode of transmission of events, a mode that is intensely visual. Throughout the text there is a discourse field of words associated with light: vision, seeing, focus, shining as well as their antonyms: murk, shadow, obscurity. This discourse field forms the underlying metaphor of the whole work. Visualisation as a narrative strategy is constantly foregrounded and brought to the reader’s attention: In every object there is inexhaustible meaning; the eye sees in it what the eye brings means of seeing. …. Let the reader here in this sick room of Louis, endeavor to look with the mind too. At other times, Carlyle will select one of the participants in a historical event, and use him as a focaliser for the reader to visualize what is going on:Let the Reader look with the eyes of Valet Clery, through these glass doors, where also the Municipality watches……Visualisation itself is even symbolized in the text. Carlyle’s term for the Court of the Ancien Regime is L’Oeil de Boeuf, which is a symbol of an eye, as well as a description of the shape of the window in the chamber in Versailles where the Court met.

This visual aspect of the work also applies to the wonderful verbal portraits Carlyle gives of the various personages of the Revolution; and it’s probably best to just give a selection here:

Mirabeau

Shining though such soil and tarnish, and now victorious effulgent and oftenest struggling, eclipsed, the light of genius itself is in this man, which was never yet base and hateful, but at worst was lamentable and loveable with pity.

Anacharsis Clootz

Him mark, judicious Reader. … hot metal, full of scoriae, which should and could have been smelted out, but which will not. He has wandered over the terraqueous planet seeking, one may say, the Paradise we lost long ago.

Marat

Marat is no phantasm of the brain, or mere lying impress of Printer’s Types, but a thing material, of joint and sinew, and a certain small stature: ye behold him there, in his blackness in his dingy squalor, a living fraction of Chaos and Old Night, visibly incarnate, desirous to speak…

Visualisation is not simply a narrative or discoursive strategy, however, but one that is closely allied to Carlyle’s method of selecting and analyzing material. He imagines himself as a kind of all-knowing historical Eye, which roams above the scenes and, like a camera, picks out salient ones for the reader to visualise:

Which event successively is the cardinal one; and from what point of vision it may best be surveyed; this is a problem. Which problem the best insight, seeking light from all possible sources, shifting its point of vision whithersoever vision or glimpse of vision can be had, may employ itself in solving; and be well content to solve in some tolerably approximate way.

3. Language and history

Men’s words are but a poor exponent of their thought; nay their thought itself is a poor exponent of the inward unnamed Mystery, wherefrom both thought and action have their birth. No man can explain himself, can get himself explained; men see not one another but distorted phantasms which they call one another.

Modern historiographers aspire towards a transparency of text, in which the information presented is not obscured by the means used to convey the information, i.e.: the language. They work under the assumption that language is capable of being a servant of meaning; this is the assumption underlying von Ranke’s famous dictum, that history must simply show wie es eigentlich gewesen ist – what actually happened. Carlyle’s historiography is entirely different, because Carlyle, as a supreme linguistic artist, is under no illusion that language is not also the creator of meaning, that it can ever be totally transparent and objective because words have subjective meanings as well as objective ones: What these two words: French Revolution may mean; for, strictly considered, they may have as many meanings as there are speakers of them. Language has only an arbitrary, symbolic relationship to the things it denotes – here Carlyle follows Locke -, which means that pure objectivity of description is impossible. This extends even to the grammatical choices available to the historiographer. In a brilliant insight Carlyle writes how the use of the past simple tense radically impinges our view of what is being described by the way the tense omits certain factors present in reality: For indeed it is a most lying thing, that same Past Tense always: so beautiful, sad, almost Elysian-sacred, ‘in the moonlight of Memory’, it seems and seems only. For observe: always one most important element is surreptitiously (we not noticing it) withdrawn from the Past Time: the haggard element of Fear!

Because words have ultimately a symbolic relationship to the things they signify, the historical work au fond also has a symbolic relationship to the history it describes. Indeed the whole text is symbolically described as a tapestry, a tissue, a weaving; and this textual weaving is emblematic of the wider weaving of the historical forces operating in reality: Story and tissue, faint ineffectual Emblem of that grand Miraculous Tissue and Living Tapestry named the French Revolution, which did weave itself then in very fact, ‘on the loud-sounding ‘Loom of Time’! As personages disappear from history, so they also disappear as characters from the text: The brave Bouille too, then vanishes from the tissue of our Story. The historical work is not only a description of history, but also a symbol of it.

3. Conclusion

One of the considerable pleasures of reading the book comes from Carlyle’s prose, which is at times lofty, at other times facetious. One of the very greatest prose stylists of the language, Carlyle’s sentences everywhere display an acute awareness of rhythm and sound: ‘Worn out with disgusts’ Captain after Captain in Royalist Moustachious, mounts his warhorse, or his Rozinante war-garron and rides minatory across the Rhine, till all have ridden, he writes of the first Emigration.He is the master of the dramatic scene, as well as the pithy historical epigram. Of Robespierre’s attempt to found a new religion in the Festival of the Supreme Being in June 1794, for example, he writes: Mumbo is mumbo, and Robespierre is his prophet. Wise wigs wag, he writes of the diplomatic storm in Europe created by the Declaration of the Rights of Man; Condorcet is described as mouton enrage, and of Mirabeau’s crucial decision to side with the Third Estate in the meeting of the Estates General which with the Revolution begins, he writes: Mirabeau stalks forth into the Third Estate.

Von Ranke wrote: To history has been assigned the office of judging the past. In his 1820 work Oliver Cromwell’s Letters and Speeches, Carlyle wrote: History is as perfect as the Historian is wise and is gifted with an eye and a soul. Carlyle displays enormous wisdom and soul in the judgments he makes, not only of the personages and events of the French Revolution, but more generally about the unfolding processes of living history itself. An example of the former is the assessment he gives of the vacuous and phlegmatic King Louis XVI, surely one of the stupidest men to ever warm a throne with his buttocks: Thy whole existence seems one hideous abortion and mistake of Nature; the use of meaning of thee not yet known.Of the latter, here are some examples of epigrams Carlyle turns out on a range of topics:

Money itself is a standing miracle.

All available Authority is mystic in its conditions and comes ‘by grace of God’.

How beautiful is noble sentiment, like gossamer gauze, beautiful and cheap; which will stand no tear and wear!

The first volume was famously put into the fire by a chambermaid, who thought it was simply waste paper, and Carlyle had to write the whole thing again from memory, which would have defeated lesser men. The French Revolution, thus, stands as a symbol of one man’s titanic endeavor, as well as a description of a people’s struggle to change their world for the better.

Man, symbol of Eternity imprisoned into Time! It is not thy works which are all mortal, infinitely little, and the greatest no greater than the least, but only the Spirit thou workest in, that can have worth or continuance.

↧

Nietzsche on Christianity

Christianity is, essentially and fundamentally, the embodiment of disgust and antipathy for life, merely disguised, concealed, got up as the belief in an 'other' life, or a 'better' life. Hatred of the world, the condemnation of the emotions, the fear of beauty and sensuality, a transcendental world invented the better to slander this one, basically a yearning for non-existence, for repose until the 'sabbath of sabbaths' - all of this, along with Christianity's unconditional resolve to acknowledge only moral values, struck me as the most dangerous and sinister of all possible manifestations of a 'will to decline', at the very least, a sign of the most profound affliction, fatigue, sullenness, exhaustion, impoverishment of life.

↧

Schopenhauer on the urge to display one's stupidity on the internet

There are very many thoughts which have value for him who thinks them, but only a few of them possess the power of engaging the interest of a reader after they have been written down.

↧

"Hijikata: The Revolt of the Body" Stephen Barber

I have recently become acquainted with a young Taiwanese butoh dancer, and I read this book to learn more about his art.

Butoh was started by the dancer Hijikata in the ruins of a bombed out Tokyo in the years immediately after WW2, although it only really came to prominence in the uneasy years of the 60’s when Tokyo was hit by student protests against Japan’s continued domination by American consumerism and militarism. As such, it is borne of death and caries the smell of revolt.

Hijikata speaks of his ideal audience as being composed of the dead, and his gestures arise from the gestures of the dying.

I would like to have a person who has already died, die over and over inside my body…I may not know death, but it knows me.

Butoh is paradox, because it aims to negate all the usual gestures of the body and all the usual parameters of dance and performance. It is a kind of anti dance, an anti performance because each performance was only given once, and Hijikata allowed very few records to be made of the performances. The first ever ‘performance’ of butoh was conducted in private with no audience. Butoh is as much meditation as dance.

This sounds like the most extreme kind of artistic masturbation, and in many ways it is. Butoh in its early days had strong links with the sex cabarets of Tokyo, and Hijikata and his collaboraters were regular performers in the porn movies and sex clubs of the Shinjuko district, largely as a means for financing his other butoh activities. One has to admire the total commitment with which Hijikata conducted his life long project to give birth to a new kind of dance; in a way his whole life was a kind of butoh performance, a revolt. Although Barber doesn’t make the comparison, I think of Andy Warhol, Hijikata’s contemporary, who epitomised the disposability and distraction of modern consumerist culture and its ghastly superficiality, while Hijikata rejected this and stood for something completely opposite: a commitment to intense concentration and total immersion. Like Warhol in his Studio surrounded by armies of assistants and hangers-on, Hijikata set up a dance studio in an old asbestos factory where he trained young dancers in the ideas and gestures of butoh. He withdrew into isolation into this Asbestos Hall just as butoh was beginning to attract attention, and rarely left it again for the last 12 years of his life.

Barber’s book gives a detailed account of the life of Hijikata, his influences (Mishima, Artaud, Genet and Lautreamont) and the various schisms that eventually took place within the world of butoh. For example, Kazuo Ohno, the other major butoh dancer of the period, Hijikata’s student and eventual butoh master in his own right, regarded butoh as something impossible for Westerners to understand, while Hijikata held that anyone could do butoh because butoh is about death, and everyone dies. Anywhere there is culture in revolt or death, there butoh is possible.

Likewise, Hijikata rehearsed for hours and meticulously choreographed each gesture, allowing no place in his work for improvisation, while Ohno had a much freeer attitude towards improvisation. The only improvised performance Hijikata ever gave was right at the very moment of his death, when he assembled the fingers of both hands and formed the outline of a ball of paper within the empty space between those fingers, rolled the ball on his chest, and then wedged it delicately under his cheek. Barber movingly calls this improvisation Hijikata’s last gift to his friend and collaborator Ohno.

Barber is also very good in the collaboration of Hijikata and the various photographers and experimental film makers he worked with. There are very few surviving films of Hijikata’s performances, as he rejected the kind of narrative or documentary linear representation a filming of a performance would necessarily involve. Butoh is not a representation of something, but a thing in itself; it negates representation, linearity.

At a butoh performance and workshop I attended in Taipei, the only entirely filmed performance of one of Hijikata’s works was screened, and the power and strength of butoh was reinforced by the flickering, disjointed images of hand held16mm. Filmed in the later half of the 20thcentury, the images and gestures looked infinitely older, atavistic, ur, like cave drawings come to life, something from the very dawn of human culture, but at the same time something suggestive of the total future death of that culture.

Hijikata’s last project involved a return to the deep north with the photographer Eikoh Hosoe, who captured images of Hijikata performing butoh amidst the rice paddies of the region, to an audience of hills, lowering clouds and birds.

↧

↧

"Empire of Signs" Roland Barthes

Barthes's book on Japan belongs to the same genre as Swift's Gullivers’ Travels, Montesquieu’s Persian Letters, Voltaire's Candide and as Barthes himself signals, Micheax's Garabagne. In this genre, travellers to a foreign country which is largely mythical, fictional, fantastic, reflect on that country's institutions, casting light on the writers' own.

This may seems a strange assertion. Japan is a real place, and Barthes really visited it. But this book is more an examination of Western thought about Japan, especially about Zen, and about Western thought itself, about how Western thought and language is ceaselessly spinning out sign systems, is in fact, an infinite supplement of supernumerary signifierswhich form the basis of Western consciousness. In Empire of Signs Barthes imagines the possibility of this ceaseless chatter ceasing, he imagines a system of emptiness, which he sees in Japanese/Zen culture.

The book is short, consisting of 26 very short chapters on different aspects of Japan: food, chopsticks, calligraphy, pachinko, the haiku, the eyelid and so on. Barthes's meditations are spot-on accurate, imaginative, fanciful, grounded in reality, and beautifully expressed.

The book is a kind of dialogue (between East and West), and this is reflected at sentence level; sentences seem to have two layers, the direct and the parenthetical:

A Frenchman (unless he is abroad) cannot classify French faces; doubtless he perceives faces in common, but the abstraction of these repeated faces (which is the class to which they belong) escapes him.

Barthes comments on his own comments. At the level of the discourse then, the book enacts that infinite supplement of supernumerary signifiers, nudging the reader into his own supernumerary signifiers.

I'm going to briefly summarize the four short chapters on haiku. Bold is chapter titles, italics are quotes from Barthes, parentheses are my comments.

It is evening, in autumn,

All I can think of

Is my parents

Buson

1. The Breach of Meaning

· the deceptive easiness of haiku

· it is intelligible but appears to mean nothing (nothing beyond itself)

· it presents its meaning simply

· in contrast with Western poetry which demands a chiselled thought, the haiku allows one to be trivial, short, ordinary

· Western poetry has unavoidably two systems of meaning: the symbol, the metaphor; and reasoning, the syllogism

· (for the Western reader) the haiku is attracted to one or other of these two signification systems

· first: we assign the haiku a 'poetic' meaning - in Western lit, 'poetic' is a symbol of the ineffable, the inexpressible-

· in this poetic meaning, everything in the haiku becomes symbolic

· second: we see the three lines of the haiku as a syllogism: rise, suspense, conclusion

· if we renounce both these systems, commentary becomes impossible: to comment on the haiku means simply to repeat it

· Western methods of interpretation fail the haiku

The West moistens everything with meaning like an authoritarian religion which imposes baptism on entire peoples.

The work of reading which is attached to it is to suspend language, not to provoke it.

How admirable he is

Who does not think "Life is ephemeral"

When he sees a flash of lightning

Basho

· the Buddhist syllogism contains four propositions:

· this is A

· this is not A

· this is both A and not-A

· this is neither A nor not-A

· this is the obstructed meaning, an impossible paradigm

· in this way, Zen wages a war against meaning

· for example, the Sixth Patriarch recommended his students to give the following answer: if questioning you, someone interrogates you about non-being, answer with being. If you are questioned about the ordinary man, answer by speaking about the master etc

· (The Sixth Patriarch is one of the major figures of Zen/Chan Buddhism, a Chinese Scholar/monk 大鑒惠能 Dajien Huineng early 8th C BCE)

· the patriarch's recommended response is designed to disrupt the paradigms of Q&A/language and therefore to imperil the search for meaning

· Zen makes the mere mechanism of meaning apparent

· the haiku is an attempt to attain a flat language, a language with no layers of meaning (Barthes calls this 'a lamination of meaning') - a first level signifier: a signifier which is matte

· all we can do with this matte signifier is scrutinize it, not solve it

· Zen and the haiku are a praxis designed to halt language

· Satori (Nirbana, enlightenment) is a suspension of the constant inner language of consciousness

· because language sums up other languages to penetrate meaning - secondary signifiers, thoughts of thoughts - Zen perceives of this a kind of jamming

· the abolition of secondary thought is one of the aims of the haiku

· the haiku attacks the symbol as a semantic operation (by refusing the possibility of a secondary language)

· it does this by measuring language, a concept which is inconceivable to the Western mind

· the Western mind always tries to make signifier and signified disproportionate (by saying a little with many words, or by saying a lot with few words)

· the haiku, on the other hand is an adequation of signifier and signified, a suppression of margins, smudges and interstices

· in the haiku, signified and signifier are measured ('get the measure' of something is also meant by this)

· the practice of saying haiku twice:

· saying it once is to give the meaning of surprise to its sudden, perfect appearance

· saying it more than twice is to simulate profundity, to postulate that meaning can be discovered in it

· saying it twice is an echo, neither singular, nor profound

There is a moment when language ceases and it is this echoless breach which institutes at once the truth of Zen and the form -brief and empty- of the haiku.

There is a moment when language ceases and it is this echoless breach which institutes at once the truth of Zen and the form -brief and empty- of the haiku....perhaps what Zen calls 'satori' is no more than a panic suspension of language, the blank which erases in us the reign of the Codes, the breach of that internal recitation which constitutes our person...('Codes' is a Barthesian term, from S/Z, meaning the reference discourses which underlie Western literature. Basically, here he means any kind of secondary thoughts.)

The echo merely draws a line under the nullity of meaning.

I come by the mountain path.

Ah! this is exquisite!

A violet!

Basho

I saw the first snow

That morning I forgot

To wash my face

(unattr)

· Western art transforms the 'impression' into a description

· in the West description - A Western genre- is the equivalent of contemplation

· two kinds of contemplation: forms of the divinity (Loyola), evangelical narrative episodes

· in the haiku, there is no metaphysics centred around a subject or around a god

· the haiku is centred around the Zen character Mu (nothing), an apprehension of the thing as an event, not as substance

· the haiku is centred on what happens to language, rather than what happens to the subject producing/receiving the language

· the haiku does not describe (this seems counter intuitive until one realises what Barthes means by ‘describe’, namely, the relationship between the sign and the signified. According to B this relationship doesn't exist in the haiku. In the haiku, language has no referent, is the essence of appearance, and an untenable moment. It is language degree Zero. Barthes calls this later in the essay an 'escheat of signification')

· it presents language as a category, as a painting, a miniature picture

· the order and dispersion of haiku, in anthologies and other texts

· on the one hand there is plethora, on the other brevity

· this creates a dust of fragmentary events with no direction or termination

· the haiku and the self, the self is nothing but the site of reading, timeless

· the haiku reflects the self

· for example, in the Hua Yen doctrine (one of the key tenets of Mahayanna Buddhism, the Buddhism of China and East Asia, the origin, one can say, of Zen), a haiku is a jewel which reflects all the other jewels in a kind of irradiation, but one with no centre

· in the West, the analogy of this is the dictionary, a play of reflections without origin

· reflection: in the West, the mirror reflects the self, in the East, a mirror reflects nothingness, it is empty

· this can be applied to everything which happens in the street in Japan

· the streets are full of incidents, which a Westerner can only read in the way he reads a haiku

· but the ability to create haiku is denied the Westerner (because of the way his consciousness is founded in language and his concept of language as a system generating secondary languages)

· the incidents observed in the street do not have anything picturesque about them, nor do they have anything novelistic about them

· novelistic: they do not contribute to the chatter which would make them descriptions or narratives

· the incidents of the street present a rectitude of line, a stroke, a gesture

· the graphic nature of Japanese life, writing alla prima

· the line does not express, but causes to exist

· there can be no hesitation, no regret, no trial and error in the stroke of the brush

· these gestures do not refer back to the self, there is no self-sufficiency, only graphism

The haiku's time is without subject: reading has no other self than all the haikus of which this self, by infinite refraction, is never anything but the site of reading.

The haiku reminds us of what has never happened to us; in it we recognize a repetition without origin, an event without cause, a memory without person, a language without moorings.

The old pond:

A frog jumps in:

Oh! the sound of the water.

Basho

4. So

· the purpose of haiku is to achieve exemption from meaning

· this is impossible in Western lit, which contests meaning only by making it incomprehensible

· the haiku resists commentary, and it's this commentary which is the most ordinary exercise of our consciousness

· the haiku doesn't instruct, express, divert- it serves none of the purposes usually attributed to literature due to its insignificance and due to the way it resists finality

· the haiku is written just to write

· in Western lit there are two basic functions: description and definition (again Barthes is using ‘describe’ in a special sense here: embellish with significations, with moralities, committed as indices to the revelation of a truth or of a sentiment)

· the haiku resists both of these

· the haiku does not describe in the sense of giving meaning to reality

· the haiku does not define except only in the sense of giving a gesture, but this gesture is only an efflorescence of the object

· the haiku only designates, it has no vibration or recurrence

· it says: 'it's that', or 'it's thus' or 'it's so', or even just 'so.'

· it's like the flash of a photo one takes very very carefully, but with no film in the camera

· the haiku is stripped of any mediation of knowledge, of possession, of nomination,

· it's like a child pointing at something and saying 'That!'

The haiku's task is to achieve exemption from meaning within a perfectly readerly discourse (a contradiction denied to Western art, which can contest meaning only by rendering its discourse incomprehensible).

The haiku is a faint gash inscribed upon time.

Nothing special says the haiku, in accordance with the spirit of Zen...nothing special has been acquired, the word's stone has been cast for nothing; neither waves nor flow of meaning.

Full moon

And on the matting

The shadow of a pine tree

In the fisherman's house

The smell of dried fish

And heat

The winter wind blows

The cat's eyes

Blink

unattr.

How many people

Have crossed the Seta bridge

Through the autumn rain?

Joko

↧

John Blofeld on Richard Wilhelm's translation of the I Ching

Those readers who positively like their oracles to be couched in terms so obscure as to be inscrutable will prefer Wilhelm's version to mine, as parts of it are obscure enough to satisfy the most ardent devotees of mystery.

↧

Fragment 2412014

In Qian Zhongshu's classic Chinese novel of 1947 Fortress Besieged the protagonist Hung Chien is teaching at a brand new university in the interior of China, far from the fighting. The university, with its admin and various departments, faculty and students, stands as a symbol of the Republic of China under KMT rule, especially during the period when Madame Chiang’s New Life Movement was in effect. Hung Chien has been appointed the lowly position of lecturer in Logic.

In Qian Zhongshu's classic Chinese novel of 1947 Fortress Besieged the protagonist Hung Chien is teaching at a brand new university in the interior of China, far from the fighting. The university, with its admin and various departments, faculty and students, stands as a symbol of the Republic of China under KMT rule, especially during the period when Madame Chiang’s New Life Movement was in effect. Hung Chien has been appointed the lowly position of lecturer in Logic.According to the school regulations, students in the College of Letters and Law had to choose one course among Physics, Chemistry, Biology and Logic. Most of them swarmed like bees to Logic because it was the easiest. – “It’s all rubbish” and not only did they not conduct experiments, but when it was cold, they could stick their hands in their sleeves and not take notes. They chose it because it was easy, and because it was easy they looked down on it, the way men look down on easy-to-get women. Logic was “rubbish”.

Chinese logic is parodied mercilessly in several places in the text, not just the peasant logic of old saws and sayings; but in other ways: the library has no books on logic; Hung Chien is preparing his course – he has never studied logic himself- from an old copy of An Outline in Logicanother faculty member has given him. But the text also gives examples of logic put forward to justify social behaviour.

Han Hsueh Yu, head of the foreign languages department, is married to a White Russian émigré he bumped into in Shanghai; he also has a fake Phd diploma he bought from a mail order catalogue in the US. He anxious to give everyone the impression that his wife is American – a highly desirable commodity – and his fake certificate a secret.

On the evening of July fourth, the last day of the final examinations, Han threw a big party for his colleagues with his wife’s name appearing on the invitation. The occasion was American Independence Day. This of course proved that his wife was indeed a genuine full-fledged American; for otherwise, how could she be always thinking about her mother country? Patriotism is not something that can be simulated. If the wife’s nationality were real, could not the husband’s academic credentials then be fake?

Now, this may appear to be only a sharp satire on academic behaviour, but Qian Zhongshu is on to something much more subtle and deeply buried here. This is an example of what we can call a Chinese Syllogism, which looks formally like a perfectly reasonable syllogism, but which differs from its Western counterpart essentially in that the terms of the syllogism need not bear any relationship at all to each other, or to reality. What matters most is the appearance of a logical structure, its conformity to a linguistic formula, a syntax, rather than its content or any relationship to reality per se.

One can see how this works by splitting the language horizontally into two layers and removing the lexical layer, leaving behind only traces of the syntactical.

If X then Y

X of course proves Y, for otherwise how could Z happen?

If X, then couldn’t it also be Y?

One can then replace the integers with any random vocabulary:

If I sneeze, then someone is thinking about me.

The fact that all foreigners have big noses of course proves that they smell, for otherwise how could it not be that we can all smell them?

If you have been abroad as foreign student and returned to China, couldn’t it also be that you are a suspicious character?

Whether we do this in English or in Chinese matters not a jot to the underlying point which is that the formal syntactical structure of the utterance matters more than the viability of its content. Its air of authority and the declarative way with which it is uttered forestalls any attempt at disagreement, while the crafty use of negative interrogatives ensures a positive answer, a confirmation of the absurd bias of the syllogism.

Normal, natural, observable causality is thus utterly traduced in favour of an arbitrary causality simply imposed upon it. It’s as if the Daoist mindset, with its steadfast refusal –inability- to form categories as it perceives the world, when faced with the demand to suddenly do so, out of sheer inexperience lumps a few hastily gleaned facts of reality together and announces a causal relationship between them.

Towards the end of his sane life, Nietzsche was playing with the idea of critiquing causality. What he means is not the underlying causality of physics per se, but the underlying concept of causality, the syntactic syllogisms, both articulated and silent, with which we make sense of cause and effect in the world. He suspected that the notion of causality was something that had to be learned first, a habit of mind, such as the habit of seeing the world in terms of space and time, concepts like causality which also at some point in the development of human consciousness had first to be learned:

This belief in causality is erroneous: purpose, motive, are means of making something that happens comprehensible, practicable. The generalisation, too, was erroneous and illogical.

Notebook 34 1885

Like a child taking its very first steps, the Chinese Syllogism shows perhaps the trial and error involved in forming a useful concept of causality. It’s all a bit hit and miss.

↧